January 31, 2026

Why Textbooks? with Danielle Merritt-Sunseri

This article was first published as part of the Alveary Weekly, our weekly newsletter for Alveary members, which includes answers to member questions and commentary on various topics related to a relational education.

Living Textbooks?

Can a textbook be living? If so, what is it that makes a book living? If not, what characteristics of a textbook disqualify it? These are some deep questions that are worth discussion, but it seems like the practical decision to avoid textbooks should be pretty straightforward when Mason says things like “Books dealing with science as with history, say, should be of a literary character, and we should probably be more scientific as a people if we scrapped all the text-books which swell publishers' lists and nearly all the chalk expended so freely on our blackboards.” But then we go to her programmes to see what books she was scheduling…

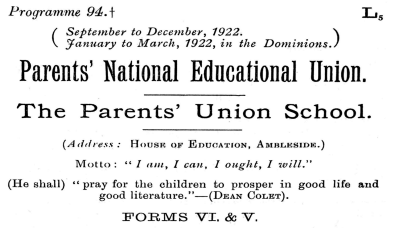

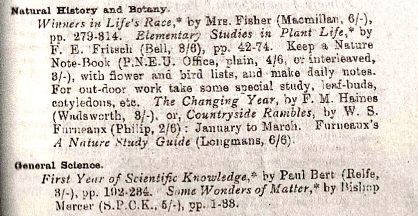

…and we notice that she was actually using textbooks in both history and science - and not just occasionally, but regularly. Here you can see samples from Programmes 94 and 92, respectively.

We see titles, such as A Text Book of Geology by Lapworth, An Introduction to the Study of Plants by Fritsch and Salisbury, and Flammarion's Astronomy,

In the interest of space, we won’t include examples of all of them here, but you can see that we have a variety of textbooks on the programmes. So, what’s going on here? We need to dig a little deeper. We need to form a larger picture to understand what she was actually doing and why she said the things she said.

.png)

Keeping Context in Mind

Just like any topic where it looks like Mason is saying or doing something that conflicts, it’s very helpful to learn more about her context. We do this by studying topics, like history of literature, history of science literature, history of British education, and history of science education. One idea that begins to stand out is that in her time children’s literature and even science literature were only just beginning to gain traction. They didn’t have fantasy and historical fiction and narrative nonfiction and biography and all of these different genres. It was just literature - and there was a lot of disagreement as to whether the topic of modern science qualified as literature at all.

Another idea is that science was not a standard subject taught at school. It was vocational training for lower-class boys and possibly a hobby for some rich, eccentric men. It was unnecessary for girls and it was well beneath upper-class boys. What this means is that the only demand made of science textbooks at the time was that they were sufficient for the purpose of job training for a group of people who were considered to be too vulgar to be in need of literature. (Jane Austin fans will recall Emma’s snobbish consideration of poor Robert Martin.)

Science for All

Enter Charlotte Mason. Mason believed that science education was important for everyone by right of being a person. And we see throughout her programmes that a standard book that approached the subject very systematically was actually favored by her. So, it wasn’t simply those characteristics of textbooks that she had a problem with. What she was against very consistently were utilitarian books and ‘hortatory’ lectures intended to train drones rather than educate persons. This was an obvious problem with those textbooks that ‘swell publishers’ lists.’ Persons need ideas that are communicated well by passionate, knowledgeable minds. Can a textbook do that? As we have seen in her programmes, she seemed to think so. She chose those that focused on principles and ideas rather than vocational training, were written in language that was comfortable and relevant to her students, and shared the wonderful ideas of science directly from one mind to another. Stories and nature immersion were still vital components of science education for her even in the upper Forms, but they alone did not make a complete curriculum.

We want the textbooks and resources that we choose in our own place and time to be comparable to those that Mason selected. Whether Alveary high school students select Chemistry, Biology, Botany, or Physics, we want them to learn from passionate, knowledgeable persons who share principles and ideas in thoughtful, well-organized language. The Alveary team is here to guide you through these exciting high school years and we hope you will consider joining us at this year’s conference where we will dig deeper into conversations just like this one.

Notes & Further Resources

Early 20th c science textbooks

https://digital.library.pitt.edu/islandora/object/pitt%3A00ace7344m/viewer#page/3/mode/1 up

https://digital.library.pitt.edu/islandora/object/pitt%3A00ace1765m/viewer#page/3/mode/1 up

https://digital.library.pitt.edu/islandora/object/pitt%3A00abu6395m/viewer#page/1/mode/ 1up

https://digital.library.pitt.edu/islandora/object/pitt%3A00z423660m/viewer#page/17/mode /1up

Historical context

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/loi/1098237X

Baker, Tunis. “Teaching the Scientific Method to Prospective Elementary School Teachers.” Science Education. 29.2(1945). 79-82.

Baker, Arthur O. “Serving Cleveland and the Nation Through Science Teaching.” Science Education. 29.2(1945). 86-88.

Otis, Laura, Ed. “Literature and Science in the Nineteenth Century: an Anthology.” Oxford University Press: New York, 2002.

Schatzberg, Walter, Ronald A. Waite, and Jonathan K. Johnson, Ed. “The Relations of Literature and Science: an Annotated Bibliography of Scholarship, 1880-1980.” The Modern Language Association of America: New York, 1987.

Trugman, Ann. “Victorian Ideology and Children’s Literature, 1870-1914.” Thesis, North Texas State University. 1969. Accessed online 22 January 2022:

https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc131179/m2/1/high_res_d/n_04002.pdf

Gillard, Derek. Education in England: a history. 2018.

http://www.educationengland.org.uk/history accessed online 8 April 2021.